Dongguan UFine Daily Chemical Co.,Ltd.

- All

- Product Name

- Product Keyword

- Product Model

- Product Summary

- Product Description

- Multi Field Search

Views: 222 Author: Tomorrow Publish Time: 11-29-2025 Origin: Site

Content Menu

● What is Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)?

● Manufacturing Process of PVA Films

● How PVA Functions in Laundry Pods

● Health and Safety Considerations

● Alternatives to PVA-Based Pods

● Regulatory Landscape and Future Outlook

● FAQ

>> 1. What exactly is the main component of laundry pod film?

>> 2. How is PVA film produced for pods?

>> 3. Does PVA fully biodegrade after dissolving?

>> 4. What risks do PVA microplastics pose?

>> 5. What pod alternatives reduce plastic use?

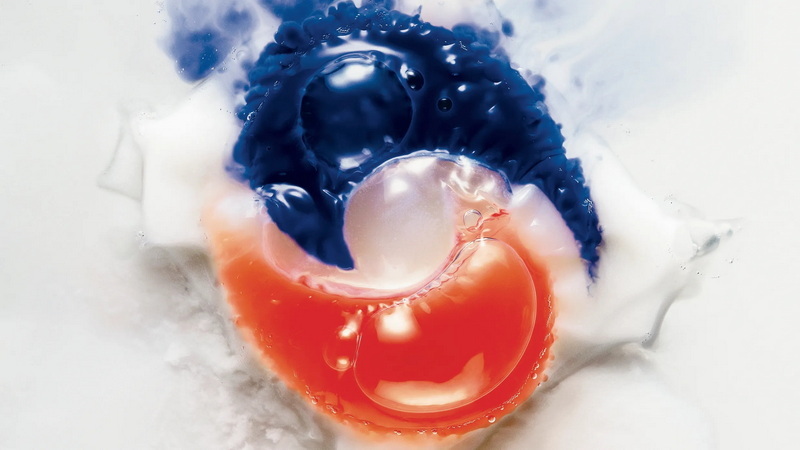

Laundry pods offer convenient, pre-measured doses of detergent for effective cleaning. Consumers often question the composition of the plastic-like film encasing these pods and its safety for the environment. The plastic in laundry pods consists primarily of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a synthetic water-soluble polymer derived from petroleum. PVA dissolves in water during washing but persists as microplastics in wastewater, raising concerns about long-term ecological impacts.[11][12]

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), sometimes called PVOH, forms through polymerization of vinyl acetate followed by hydrolysis. Manufacturers start with polyvinyl acetate, treating it with methanol and a catalyst like sodium methoxide to yield PVA powder. This powder dissolves in solvents and heats into thin films suitable for pod casings. PVA's water solubility stems from its hydroxyl groups, allowing hydrogen bonding with water molecules.[1]

PVA differs from common plastics like polyethylene, which resist water. Its structure enables dissolution at temperatures above 20°C, typical in washing machines. Producers tailor PVA grades by molecular weight and hydrolysis degree for strength and solubility balance. Low-hydrolysis PVA resists oils in detergents, while fully hydrolyzed versions dissolve faster.[3]

PVA film production begins with extrusion, melting raw PVA and forcing it through a die into thin sheets. Cooling solidifies the film, followed by casting on drums for drying to precise moisture levels. Thickness controls range from 50-100 microns to hold detergent without premature rupture. Quality checks ensure uniformity, as variations affect pod performance.[4][3]

Automated machines handle pod assembly. Water-soluble film feeds into forming stations using vacuum or thermoforming to create cavities. Precise nozzles inject concentrated detergent, including surfactants, enzymes, and fragrances. A second film layer seals via heat or ultrasound, bonding without damaging contents. Cutters separate individual pods, with vision systems rejecting defects.[2][5]

Multi-chamber pods form similarly, separating bleach or fabric softeners for controlled release. Production speeds reach thousands of pods hourly, minimizing waste. Packaging uses moisture-proof containers to prevent humidity-induced dissolution. Strict controls maintain detergent viscosity and film integrity throughout.[4]

During washing, PVA film contacts water, swelling and rupturing within seconds to release detergent. Warm water accelerates this, ensuring even distribution on fabrics. The film fragments into tiny particles, passing through drains into sewers. Unlike solid plastics, PVA avoids clogs but enters treatment plants inadequately equipped for its breakdown.[13][11]

Detergent concentration exceeds 65% actives, reducing volume and transport emissions compared to liquids. PVA withstands handling stresses, from production to consumer use. Its oil resistance prevents leakage from internal surfactants. Post-dissolution, remnants join wastewater effluent, reaching rivers and oceans.[3]

PVA dissolves but degrades slowly without specific microbes or conditions found in few wastewater plants. Studies show up to 90% persists as microplastics, accumulating in sediments and food chains. These particles adsorb toxins like heavy metals, magnifying harm to fish and wildlife. Aquatic organisms ingest them, risking bioaccumulation up to humans.[12][13]

Landfill PVA fares worse, resisting moisture and persisting indefinitely. Annual pod use generates billions of films, amplifying pollution. Treatment plants remove some via sludge, but incineration or land application spreads residues. Emerging research links PVA microplastics to soil health declines and reduced crop yields.[11]

Regulatory views vary; the EPA deems PVA low-risk based on limited data, but critics demand fuller lifecycle assessments. Ocean deposits contribute to global microplastic loads, with PVA comprising notable portions in some surveys. Climate ties emerge from petroleum origins and manufacturing energy demands.[7]

PVA holds GRAS status from the FDA for indirect food contact, showing no acute toxicity in rat studies. Manufacturing ensures purity, minimizing impurities. Human exposure occurs via skin contact or inhalation of film dust, but levels stay below thresholds. Wastewater microplastics pose indirect risks through seafood consumption.[8][1]

Child safety features like bitter coatings reduce ingestion hazards, though incidents prompt packaging innovations. Allergic reactions to PVA remain rare. Detergent enzymes inside pods present greater acute risks if mishandled. Overall, PVA prioritizes use safety over disposal concerns.[4]

Brands label pods "biodegradable" or "plastic-free," leveraging PVA solubility. Dissolution differs from biodegradation, requiring OECD 301 tests unmet by PVA. "Eco-friendly" assertions ignore microplastic outputs. Certifications like EU Ecolabel scrutinize such claims, pushing transparency.[7][13]

Cold-water dissolution marketing overlooks residue in low-temperature washes. Comparisons to sheets or strips mislead, as many use similar PVA. Consumer education counters greenwashing, empowering informed choices. Independent testing exposes discrepancies between claims and realities.[10]

Powder detergents in cardboard boxes eliminate films entirely. Liquid refills cut plastic via reusable bottles. Biodegradable starch-based films emerge, fully breaking down in soil. Laundry sheets dissolve slower but avoid pods' microplastic spikes. DIY concentrates offer customization.[14]

Innovations include cellulose films and enzyme pods without synthetics. Brands like Blueland pioneer tablet formats. Scaling these requires cost reductions and performance matching. Policy incentives accelerate adoption, targeting zero-plastic laundry by 2030 in some regions.

Agencies like the FTC monitor advertising, fining unsubstantiated claims. EU REACH mandates PVA registration, probing persistence. Bans on non-soluble plastics spur PVA reliance, ironically worsening microplastics. Research funds target PVA-eating bacteria for wastewater.[7]

Industry pledges phase-outs by 2025 falter amid demand. Consumer shifts to alternatives pressure reform. Lifecycle analyses guide sustainable redesigns. Transparent labeling builds trust, aligning products with planetary limits.

The plastic in laundry pods, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), enables convenient dissolution but generates persistent microplastics, challenging eco-claims. Manufacturing precision ensures efficacy, yet environmental persistence demands scrutiny. Health profiles reassure direct use, but indirect exposures warrant monitoring. Sustainable shifts to true biodegradables and refills mitigate impacts, urging informed consumer and regulatory action for cleaner futures.[12][3][11]

The primary material is polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), a synthetic polymer engineered for water solubility.[11]

PVA starts as powder, extrudes into sheets, dries precisely, then forms via vacuum into pods, fills, seals, and cuts.[3][4]

No, it fragments into microplastics persisting in environments without specialized degradation conditions.[13][12]

They adsorb toxins, harm aquatic life, enter food chains, and pollute soils and waterways.[7]

Powders, refills, starch films, and sheets minimize or eliminate synthetic polymers.[14]

[1](https://www.reddit.com/r/askscience/comments/bmshky/how_is_polyvinylalcohol_pva_made_into_dishlaundry/)

[2](https://www.polyva-pvafilm.com/how-does-laundry-detergent-pods-packaging-machine-producing-pods.html)

[3](https://www.polyva-pvafilm.com/the-manufacturing-process-of-laundry-pods-and-water-soluble-films.html)

[4](https://www.ufinechem.com/how-do-they-make-laundry-pods.html)

[5](https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sEkmDXQjKw0)

[6](https://lifestyle.sustainability-directory.com/learn/how-does-the-manufacturing-process-of-detergent-pods-affect-their-overall-carbon-footprint/)

[7](https://shawinstitute.org/2024/02/15/the-controversy-over-pva-detergent-pods-what-it-all-means/)

[8](https://www.cleaninginstitute.org/pva)

[9](https://stppgroup.com/still-struggling-with-mixed-laundry-how-laundry-pods-compartment-technology-solves-it-all-at-once/)

[10](https://www.consumerreports.org/environment-sustainability/what-is-polyvinyl-alcohol-what-is-pva-used-for-a1054051485/)

[11](https://www.ufinechem.com/are-laundry-pods-plastic.html)

[12](https://www.ufinechem.com/are-laundry-pods-made-of-plastic.html)

[13](https://www.blueland.com/articles/are-laundry-pods-and-sheets-plastic)

[14](https://www.reddit.com/r/ZeroWaste/comments/1auz1q0/psa_to_everyone_please_dont_use_laundry_sheets_or/)

The Ultimate Guide to Using Laundry Pods Effectively: Insights from a Leading OEM Manufacturer

Why Global Brands Now Prefer Laundry Pods – Insights From Our OEM Factory in China

Why Laundry Pods Do Not Dissolve (And How To Fix It Every Time)

Why Homemade Laundry Soap Is Bad in 2026 (And What Smart Laundry Brands Should Use Instead)

8 Best Smelling Laundry Detergents in 2026 (Expert Guide + OEM Insights)

8 Best Detergents for Black Clothes in 2026 (Expert Guide + OEM Insights)